Constructed documents and visual representation

The notion of photographs as unvarnished windows onto reality has long been contested. It has been said that photographs are an artificial construct, an artifice¹, and so the question arises as to how much of a record any photograph is as a document of truth. I contend that it cannot really be true, unless of course you regard truth as subjective.

The creation of any photograph involves a series of choices which include viewpoint, timing, lens selection and image format. These decisions, along with the photographer’s perspective and potential bias, significantly shape the final image. Add context and presentation into the mix and it becomes clear how the viewer can be presented with a very specific statement which may or may not reflect an objective reality. Familiar territory to any student of photography.

Photography has also been variously described as “a heterogeneous complex of codes”² and “neither creation nor memory, but documents”³.

I’m drawn to it’s potential for semiotic representation and as a document of information open to significant subjectivity and, at times, misrepresentation.

These aspects to photography become particularly relevant in fields such as photojournalism, documentary photography and forensic images where ethics and accuracy are paramount but is also interesting to explore on a more general level.

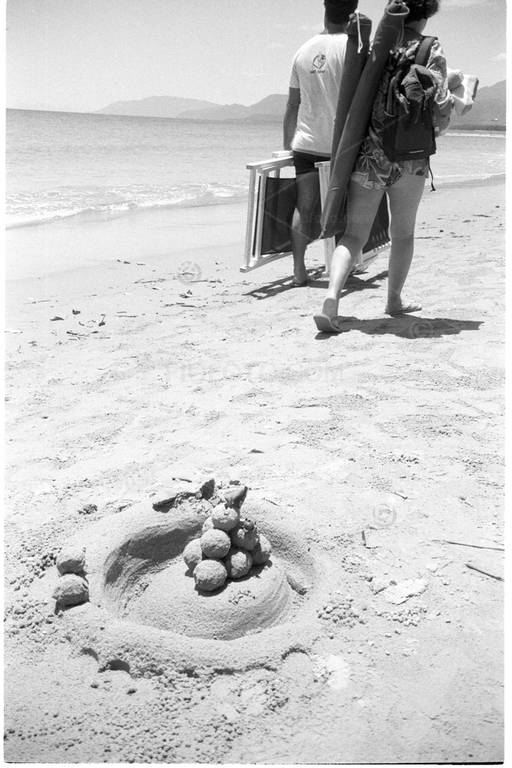

When one releases the camera shutter on a scene, a kind of facsimile of the world is created in two dimensions. But however much one wishes, it can only be considered as an interpretation, shaped by the photographer’s eye and intent or perhaps to prompt a story constructed by the viewer’s perspective.

Embracing imperfection I often work spontaneously with simple equipment, resulting in rough photo sketches attempting, in a brief moment, to extract some essence of the view before me. PJ, 2023

1. David Hockney (UK & USA) has several critical comments on photography, referring to it as a limitation or artifice.

“On Photography” by Susan Sontag, 1977, USA.

2. Burgin, Victor (1982b): ‘Looking at Photographs’. In Burgin (Ed.), op. cit., pp. 142-153

3. Takuma Nakahira “The Illusion Called the Documentary: From the Document to the Monument,” published 1972, Japan.

Shaping the story

In judicial proceedings, photographic evidence typically serves as supplementary or corroborative support for other forms of evidence. However this case study presents an exceptional instance, where photographic evidence formed the basis for the prosecution’s prima facie case in a criminal trial, highlighting potential pitfalls in relying solely on visual data and the critical role of rigorous forensic methodology.

The case involved the demise of an individual discovered on a busy roadway. A significant delay preceded police involvement, including a week before the commencement of a forensic autopsy. Subsequently, a police officer captured a series of snapshots of the deceased at the mortuary, a subset of which were later introduced as evidence by the prosecution. These images became the cornerstone of the prosecution’s case against several individuals charged with murder.

The prosecution’s theory centred on a specific mark observed on the deceased, alleging a visual resemblance to a common implement often found in the trunks of vehicles. This hypothesis, presented to the jury, lacked corroborative witness testimony regarding the suspects’ direct involvement in the incident. Consequently, the weight of the prosecution’s case appeared to disproportionately rely on the photographic evidence obtained by the police officer more than a week after the event.

Despite police testimony regarding the veracity and accuracy of the photographs, and the prosecution’s enthusiastic presentation of the evidence as supportive of their theory, a critical review revealed significant shortcomings in the photographic methodology. The mortuary photographs, captured on 35mm film (it was pre-digital age) using a rudimentary “flash on camera” technique, exhibited poor quality and lacked essential details such as a measurement scale. Information relating to camera-subject distance and precise lens focal length was also vague.

These images fell considerably short of professional forensic photographic standards, lacking the necessary detail and control for objective analysis. At best they could only be regarded as a basic aide-mémoire and it was not possible to definitively determine the shape and size of the mark in question based on these photographs.

The prosecution also introduced additional photographs comparing the mark on the deceased to the suspect implement, generated by a police officer. Crucially, no independent mechanical fit analysis conducted by a qualified forensic scientist was presented to support this visual comparison.

The defence argued that the prosecution’s hypothesis, founded on the limitations of the photographic evidence, could not be substantiated beyond a reasonable doubt. While the jury initially returned a guilty verdict, a subsequent appeal resulted in the acquittal of the defendants.

This real-life case, with certain details omitted for legal and privacy considerations, serves as a compelling illustration of the inherent potential for bias and misinterpretation within photographic evidence. The case shows the importance of adhering to rigorous scientific methodologies and utilising the expertise of qualified forensic photographers, accompanied by independent analysis where necessary, to guarantee the integrity and reliability of such evidence within judicial proceedings.

Moreover, this case underscores the critical role of context and presentation in shaping how photographs are perceived, potentially influencing legal outcomes and public opinion.